Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy secondary to non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

Article information

Abstract

We present a case series of two patients who developed unilateral cranial nerve III (CNIII) palsy following non-aneurysmal SAH (NASAH). Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) can present with various signs and symptoms. Early diagnosis is paramount to determine treatment course. Thus, clinicians must be aware of the variable clinical presentations of this condition. Two patients were admitted to a single institution for SAH. Patient 1, 52-year-old male, presented with headache, left eye ptosis, and painless diplopia. A non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a SAH within the left sylvian fissure and blood surrounding the mesencephalon and falx. Patient 2, 70-year-old male, presented with mild headache, acute onset of blurry vision, and right eye ptosis. A non-contrast head CT demonstrated a diffuse SAH predominantly in the Sylvian and suprasellar cisterns. Patients were admitted to the neuro intensive care unit and underwent diagnostic angiograms to identify possible aneurysms. Magnetic resonance imaging and angiograms for both patients were negative. Patients were managed with best medical therapy and followed up in the outpatient setting. Unilateral CNIII palsy in the setting of NASAH was identified in both patients. Diagnostic angiograms were negative for aneurysms; therefore, SAH were determined to be spontaneous. We propose that unilateral CNIII palsy is a possible sign of NASAH.

INTRODUCTION

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is caused by multiple etiologies and can present with various signs and symptoms [23]. A quick and early diagnosis is paramount in determining an effective course of treatment. As such, physicians must be aware of the diverse clinical presentations of SAH. A stat head computed tomography (CT) should be done if SAH is suspected [28]. Isolated cranial nerve III (CNIII) palsy in the setting of SAH is most commonly seen secondary to compression by intracranial aneurysm, especially those of the posterior communicating artery (PCoA), internal carotid artery, and basilar artery. In fact, an isolated CNIII palsy is one of the clinical hallmarks of a PCoA aneurysm [18]. Another common cause of CNIII palsy is brain stem ischemia and trauma, usually due to severe head blows [3,17,23]. Signs and symptoms of CNIII deficits usually recover over a period of weeks to months. Symptoms that are present after six months usually persist over time [3]. In cases of CNIII palsy caused by intracranial aneurysms, recovery of CNIII function usually occurs for those who undergo neurosurgical intervention (i.e. clipping, coiling, and/or endovascular embolization). However, recovery may be incomplete [2,3,5,9,12,16]. In cases of CNIII palsy caused by ischemia, recovery of CNIII function usually occurs within three to six months [3]. Patients with CNIII palsies caused by trauma may also experience spontaneous resolution; however, prognosis is worse than those with CNIII palsies due to ischemic lesions [3].

At present, cerebral angiography remains the gold standard test for evaluation of intracranial aneurysm [2,14]. The reason for continued use of this test for detection of aneurysm in the setting of CNIII palsy is due to the fact that contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or CT angiography (CTA) has a 95-98% sensitivity [2,14]. Repeat angiography after 4-6 weeks may be useful to detect occult aneurysms that were not observed on initial angiography due to small aneurysm size, technical or reading errors, and/or aneurysm obscuration due to hematoma, vasospasm, and/or thrombosis in the aneurysm sac [21,23,25]. Up to 24% of all SAH patients with negative angiography are found to have an aneurysm on repeat angiography [8,23,25,26]. Occasionally, a third angiogram is performed after two to three months, however, this is likely unnecessary in the majority of patients [21,25,26]. This manuscript presents a case series of two male patients, at a single institution, who developed unilateral CNIII palsy following non-aneurysmal SAH (NASAH). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case series reporting this particular sequala for NASAH.

DESCRIPTION OF CASES

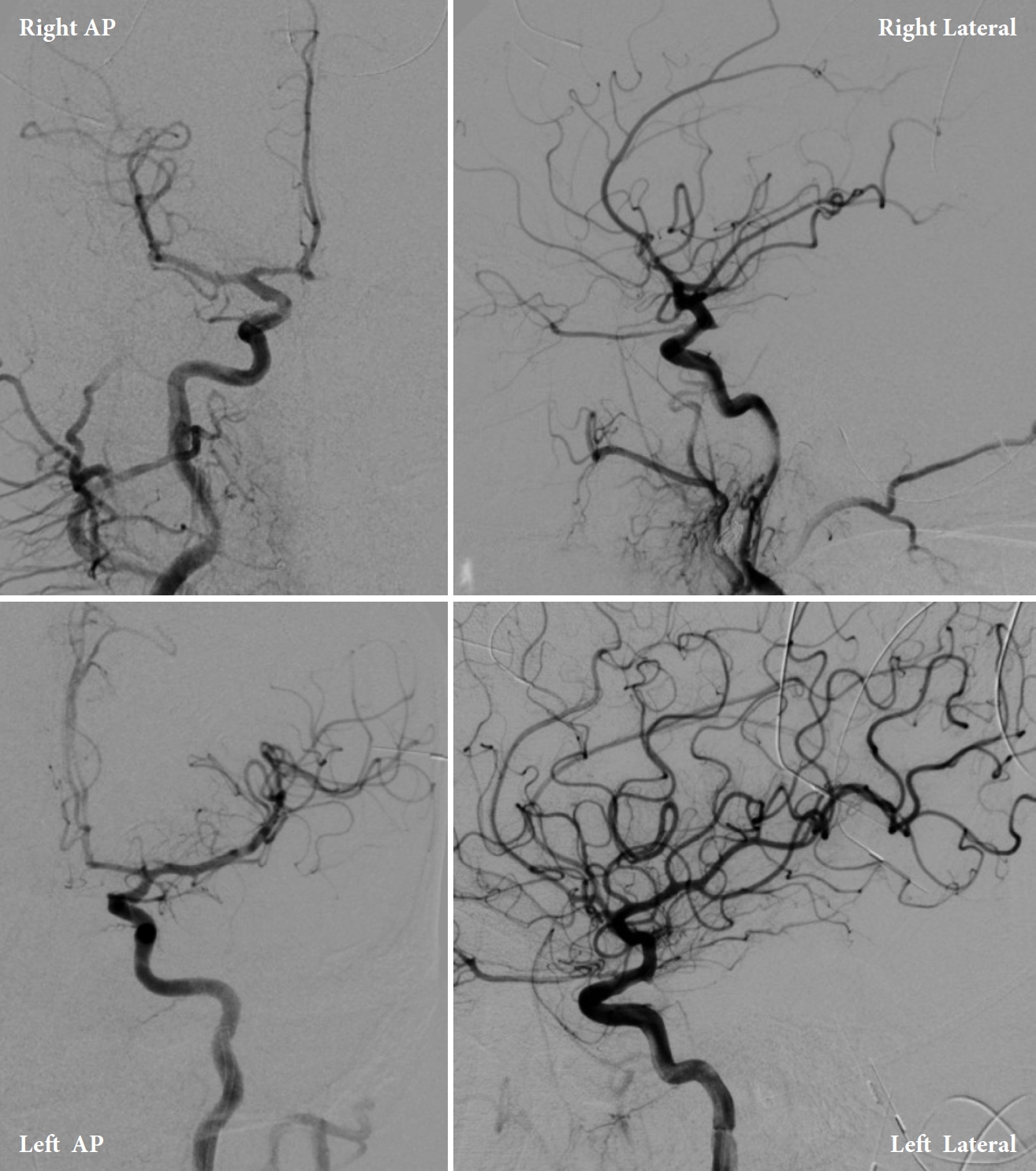

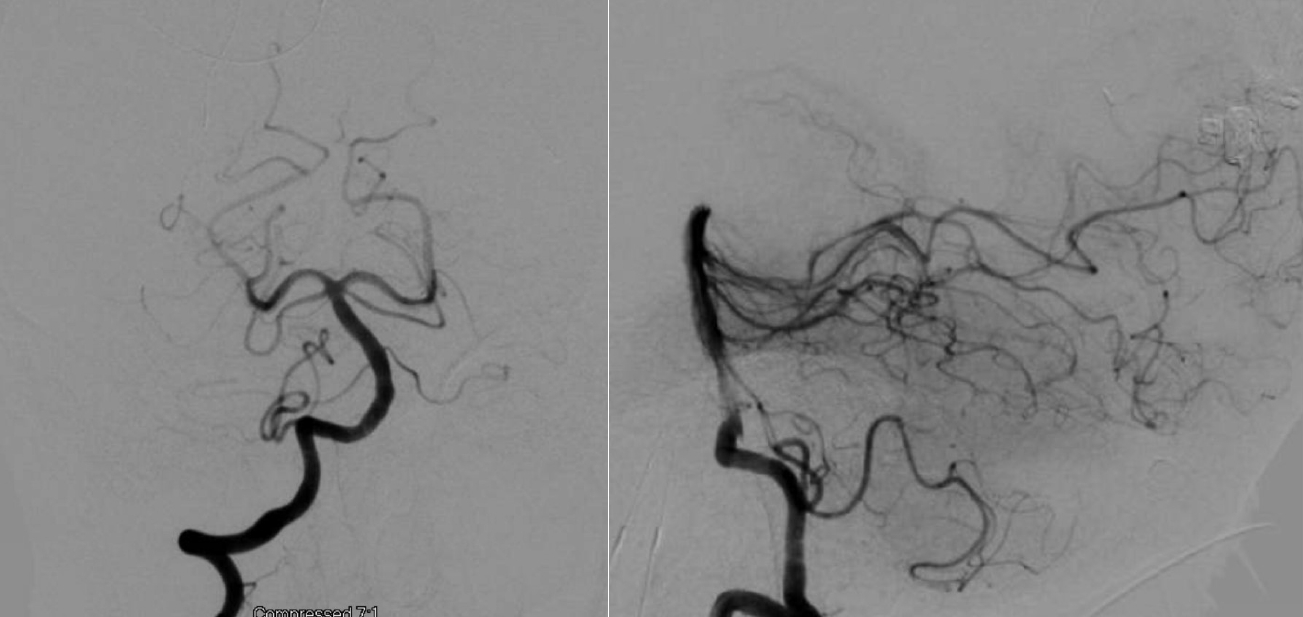

Patient 1 is a 52-year-old male with a medical history of hypertension who presented to an outside hospital (OSH) with left eye droop and blurry vision. Five days prior to admission, the patient began having a mild headache with intermittent dizziness and neck pain. On the day of admission, the patient developed a worsening headache, one episode of emesis, left eye drooping, and double vision in the morning. A non-contrast head CT demonstrated SAH within the left sylvian fissure and blood surrounding the mesencephalon and the falx. CT angiography and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) results were unremarkable (Figs. 1, 2). Patient 1 was subsequently transferred to our comprehensive stroke center for angiogram with possible intervention due to concern for a potential aneurysm given his imaging findings and symptoms of CNIII palsy. Upon arrival, the patient was neurologically intact, barring left eye ptosis and signs of CNIII palsy. The right pupil was 3 mm, round, and reactive to light and accommodation. The left pupil was 5 mm, round, and non-reactive in a down and out position consistent with complete left CNIII palsy. Patient 1 denied any previous neurologic deficits or stroke-like symptoms. He was on no anticoagulation.

CT Angiography of the posterior circulation demonstrating no evidence of AVM or aneurysm. CT, computed tomography; AVM, arteriovenous malformations

Digital subtraction angiogram of the posterior circulation demonstrating no evidence of AVM or aneurysm (Patient 1). AVM, arteriovenous malformations

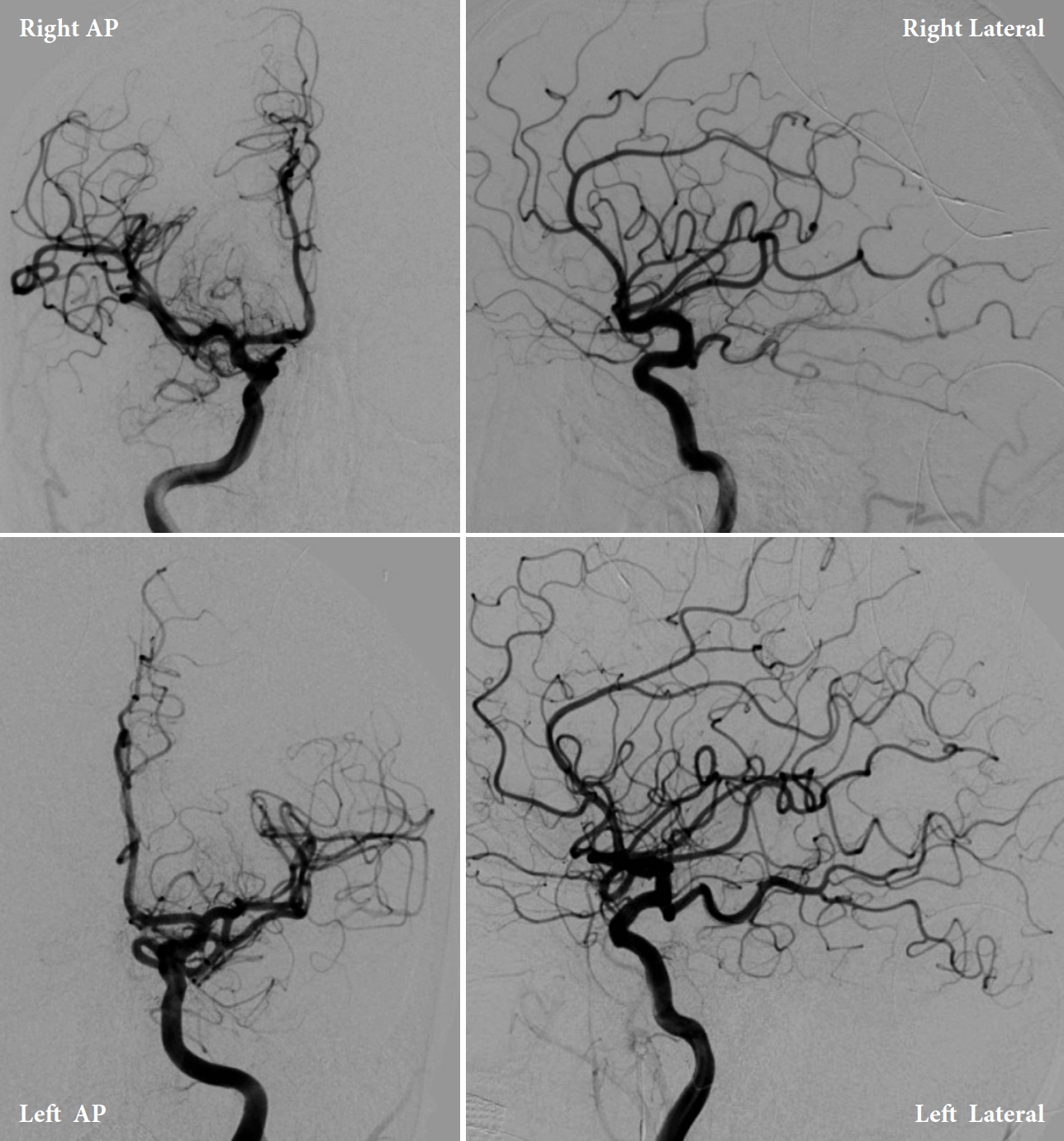

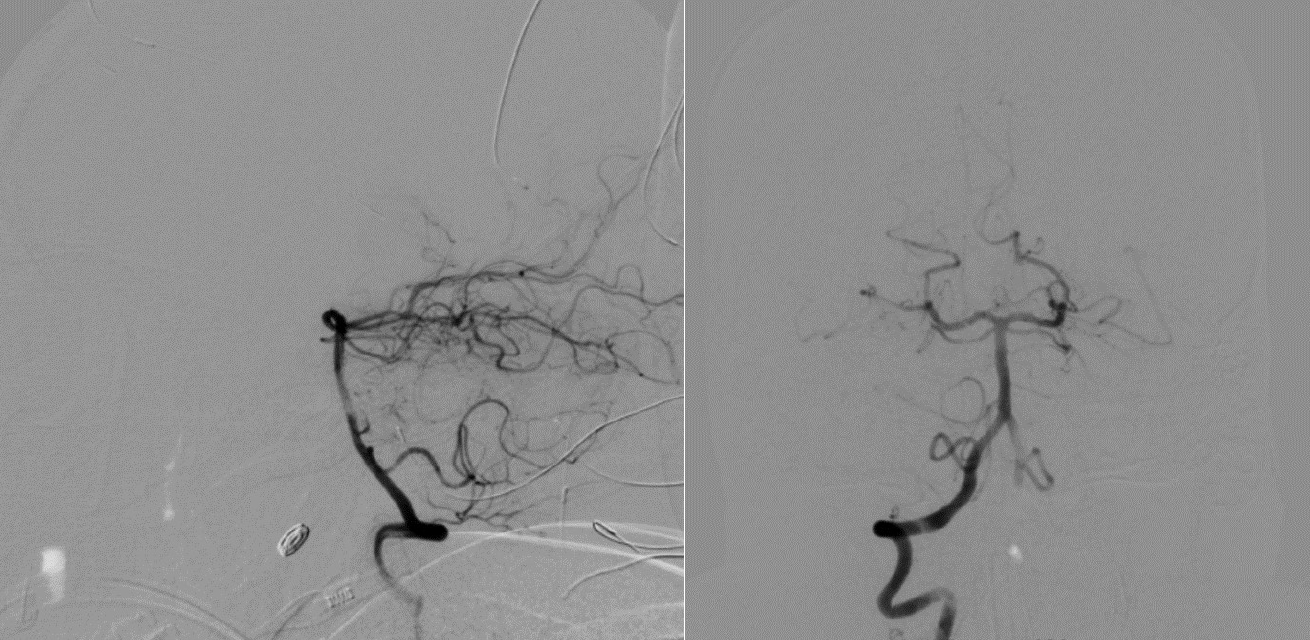

Patient 2 is a 70-year-old male former smoker with a medical history of hypertension who presented to an OSH with a headache, right eye ptosis, and swelling with no known precipitating factors. He was not on anticoagulation medications. Of note, the patient recollected having had a very minor fall, bumping the right side of his forehead on a wall at home two days prior. This head bump is unlikely to have resulted in any significant pathology apart from a minor forehead abrasion. Patient 2 stated that the swelling of his eye and inability to open it happened the same day after hitting his head on the wall. Therefore, he attributed these symptoms to the injury. Patient 2 denied any previous neurologic deficits or stroke-like symptoms. He was not on anticoagulation medications. A non-contrast head CT at OSH demonstrated a diffuse SAH, predominantly in the Sylvian and suprasellar cisterns. A CTA of the head and neck was obtained at OSH, which did not reveal any evidence of a cerebral aneurysm (Fig. 3). Further work-up with MRA and DSA found no abnormal findings (Figs. 4, 5). However, given the location of symptoms, there was still concern for an underlying cerebral aneurysm as a cause of the SAH. The patient was then transferred to the primary stroke center for an angiogram with possible intervention. On arrival, the patient was neurologically intact except for a right eye ptosis, dilated and nonreactive right pupil (5 mm vs. 2 mm in left eye), and diplopia consistent with complete right CNIII palsy.

CTA demonstrating no evidence of AVM or aneurysm. CTA, computed tomography angiogram; AVM, arteriovenous malformations

MRA demonstrating no evidence of AVM or aneurysm. MRA, magnetic resonance angiogram; AVM, arteriovenous malformations

Digital subtraction angiogram of the posterior circulation demonstrating no evidence of AVM or aneurysm (Patient 2). AVM, arteriovenous malformations

Upon arrival to the primary stroke center, both patients were admitted to the neuro ICU and underwent diagnostic internal carotid artery angiograms to identify possible aneurysms (Figs. 6, 7). Both angiograms were negative, and the patients were managed with best medical therapy. Both patients received an MRI of the brain and cervical spine with and without contrast during admission that were negative. After two days, Patient 1 developed a contralateral (right) fixed dilated 5 mm pupil without any extraocular muscles palsy. He also continued to have a fixed and dilated left pupil; therefore, Patient 1 developed bilateral CNIII palsy. Both patients remained hospitalized in the ICU for 7 days with stable neurological examinations. Transcranial dopplers (TCD) were negative for vasospasm. The patients were discharged with no further complications but without any improvement of CNIII palsy signs and symptoms. Both patients were given a follow-up appointment for a repeat vascular imaging after 3 months. Patient 1’s results were completely negative, and his symptoms resolved shortly before this time point. Patient 2’s repeat MRI and MRA were negative; however, he had no improvements in visual symptoms.

DISCUSSION

CNIII has two major components consisting of: 1) outer parasympathetic fibers responsible for controlling the ciliary muscles and sphincter pupillae and 2) the inner somatic fibers that innervate the levator palpebrae superioris and four extraocular muscles (inferior oblique, superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus) [19]. Common causes of CNIII palsy include: vascular ischemia, trauma, neoplasm, hemorrhage, and congenital abnormalities. Presenting symptoms comprise ptosis, ocular deviation in a “down and out” position, fixed and dilated pupil, and diplopia. The lab workup for CNIII palsy involves obtaining blood pressure recordings, complete blood counts (CBC), HbA1C, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and imaging studies using CTA or MRI, particularly if an aneurysm is suspected [19]. Isolated CNIII palsy, in particular, is often caused by aneurysmal compression, arterial compression, ischemia, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and trauma [20,30]. Rarer causes of CNIII palsy may also include meningitis, pituitary apoplexy, and even stroke [10,13,24].

Subarachnoid hemorrhages occur most often due to the rupture of an aneurysm or vascular malformation. However, the underlying cause is often unidentifiable in a number of cases [6]. These patients are typically divided into two groups based on the blood distribution indicated by brain imaging and clinical prognosis [6,29]. The first group is perimesencephalic SAH (PM-SAH) and is characterized by the presence of blood in the perimesencephalic cisterns as well as the basal parts of the sylvian fissures. These patients generally have good outcomes along with a lower risk of rebleeding [11,29]. The second group is non-perimesencephalic SAH (NPM-SAH) and has a more diffuse distribution extending beyond the regions implicated in PM-SAH. NPM-SAH patients generally endure a more aggressive clinical course and exhibit higher rates of complications [6,7].

Focal neurological findings are very rarely observed in patients presenting with PM-SAH. A 1985 study conducted in Sweden reported that only 10 of 127 PM-SAH patients had focal neurological deficits including hemiparesis, leg paresis, and facial and abducens nerve palsies [4]. Complete and isolated CNIII palsy involving the pupil has rarely been reported as a complication of PM-SAH. A 1993 retrospective study reported good prognosis and symptom resolution for 64% of patients presenting with aneurysmal SAH, relative to patients with nonaneurysmal PM-SAH, of which 100% demonstrated favorable outcomes at 8-months follow-up [27]. These findings contrast with the cases presented in this report with only one patient demonstrating signs of improvement. However, it is important to acknowledge that our observations are based on 3- (Patient 1) and 4- (Patient 2) month follow-up periods. Reevaluations following a longer interval may, or may not, demonstrate new findings.

In this case series, both patients presented with NASAH that extended above the membrane of Liliequist; therefore, beyond the mesencephalon. A possible hypothesis underlying these symptoms is that hemorrhagic byproducts could have irritated the patients’ oculomotor nerves, thereby causing their respective deficits. We identified four case reports of isolated CNIII palsy secondary to NASAH in the literature [1,15,22]. However, these patients all ultimately reported resolution of their neurologic symptoms. In the present case series, only Patient 1 demonstrated resolution of neurologic sympt oms while Patient 2 still has persistent symptoms of CNIII palsy. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no published cases of isolated CNIII palsy secondary to NASAH that report lack of improvement in symptoms despite optimal medical treatment. Furthermore, Patient 1’s unilateral visual symptoms advanced to bilateral symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, we could not identify any reported cases of isolated CNIII palsy secondary to NASAH that eventually progressed to bilateral CNIII palsy. In the setting of an isolated CNIII palsy, physicians should consider NASAH as part of their differential to ensure prompt detection and initiation of treatment. In addition, NASAH should be given strong consideration in patients that initially present with unilateral CNIII palsy and progress to bilateral CNIII palsy. The cases presented in this report indicate that the neurological deficits associated with this condition may be irreversible, unlike the favorable prognosis previously reported in literature.

CONCLUSIONS

Two patients were identified to have had unilateral CNIII palsy as their only focal neurologic deficit. Non-contrast head CTs demonstrated SAH, and MRI, MRA, and diagnostic angiograms were negative for aneurysms. Therefore, the investigators concluded that these patients had isolated CNIII palsy in the setting of NASAH. Only one patient showed resolution of neurologic symptoms after exacerbation from unilateral to bilateral CNIII palsy. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, advancement to bilateral symptoms, as in the case of Patient I, and non-resolution of symptoms, as in the case of Patient 2, have not been previously reported; thus, the authors suggest that isolated CNIII palsy may be a presenting sign of NASAH that clinicians should be aware of.

Notes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.