Role of surgery in management of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas

Article information

Abstract

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVF) are abnormal connections between intracranial arterial and venous systems within the dural layers. Intracranial DAVFs are rare but can occur wherever dural components exist. The pathogenesis of DAVFs is controversial. Venous hypertension is considered as a main cause of clinical symptoms which are subclassified into asymptomatic, benign and aggressive manifestations. To date, several classification schemes have been proposed to stratify the natural course and risks of DAVFs. Currently, endovascular therapy is the main treatment modality. Moreover, the use of radiosurgery and radiotherapy has been limited. Open surgery is also selectively performed as a main treatment modality for specific types of DAVFs and an adjunctive modality for the endovascular approach. Herein, we present a review of the general perspectives of intracranial DAVFs with an emphasis on the role of surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVFs), also referred to as dural arteriovenous malformations, are abnormal connections that develop between the arterial and venous systems located within the dura of the brain. Intracranial DAVFs account for approximately 10-15% of all intracranial arteriovenous malformations [23,30]. The arterial supply is mostly derived from meningeal arteries, pachymeningeal branches of cerebral arteries, and transosseous dural branches of scalp arteries [64]. Direct arterial flow drains either into the venous sinus system or the cortical veins via fistulous points. This abnormal connection results in venous hypertension and the manifestation of related clinical symptoms [78]. Currently, three therapeutic options for DAVFs are available. Development in endovascular therapy has led to its emergence as the main treatment modality. Radiosurgery and radiotherapy appear to be effective for some DAVF types. Open surgery provides access routes when accessibility is limited in the endovascular intervention. However, open surgery is considered to be a primary treatment option because endovascular intervention is not feasible in certain cases. Herein, based on the literature and our database, we provide a review of the general perspectives of intracranial DAVFs and the role of open surgery among other available treatment options.

GENERAL PERSPECTIVES

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

The incidence of intracranial DAVFs is reported to be 0.15 to 0.29 cases per 100,000 person-years [1,8,42]. Although intracranial DAVFs can occur at any age, they most commonly occur in patients who are 50 to 60 years of age [7]. No sex predilection or familial inheritance was observed [82].

The pathogenesis of intracranial DAVFs has not been clearly elucidated. It is widely hypothesized that some trigger factors, such as venous thrombosis, intracranial surgery, tumor, puerperium, trauma, hypercoagulable state and congenital causes, are associated with the occurrence of DAVFs [57]. Such stressors can weaken the structures of the dura mater, resulting in ‘recanalization’ of the vessels [55,57]. Houser et al. suggested that the pathogenesis of DAVFs is related to angiogenic factors from thrombi, which may induce the proliferation of small DAVFs [30]. Terada et al. described that chronic venous hypertension without associated venous thrombosis is the most important factor for the pathogenesis of DAVFs [77]. The association of neurological manifestations with venous hypertension was first mentioned first by Lasjaunias et al. [44] Kojima et al. suggested that venous hypertension is associated with an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, which may further induce the proliferation of DAVFs [40]. A Japanese group also supported this theory with an experimental study in rats, suggesting a possible contribution of an angiogenic factor to the growth of DAVFs in patients with venous ischemia induced by venous hypertension [73]. An in-depth study showed that a VEGF receptor antagonist caused a reduction in the DAVF induction rate in rats [48].

Locations and feeders

DAVFs are thought to disrupt normal venous flow dynamics, inducing subsequent venous hypertension. Fistulas reside within the dural leaflets of various locations, including sinuses such as cavernous, transverse, sigmoid, superior and inferior sagittal, superior petrosal, straight and sphenoparietal sinuses; convexity dura; dura mater around jugular bulb, anterior condylar vein, foramen magnum/craniocervical junction, anterior and middle cranial fossa; and others such as tentorium, torcular herophili and vein of Galen. According to our database, the most common location is the cavernous sinus (CS), followed by the transverse/sigmoid sinuses (TSS) and the superior sagittal sinus (SSS).

Branches from the external and internal carotid arteries (ECA and ICA) and vertebral artery provide feeding arteries for the intracranial DAVFs. Feeders from the ECAs run through anatomically opened structures, such as a foramen, and often take a transosseous path alongside other vessels located within or adjacent to sutures [56]. Intracranial DAVFs are fed by multiple arterial feeders depending on the location. The feeding arteries of CS DAVFs are from abundant ECA and ICA branches, which include the middle meningeal, accessory meningeal, recurrent meningeal and ascending pharyngeal arteries, arteries of foramen rotundum and ovale, deep temporal arteries and meningohypophyseal trunk [28]. The feeding arteries of TSS DAVFs include the branches of the middle meningeal, ascending pharyngeal, occipital and posterior meningeal arteries [38]. Ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic arteries are the main feeding arteries of anterior cranial fossa DAVFs. DAVFs in the posterior fossa are mostly fed by the vertebral (25%) and occipital arteries (20.5%), followed by branches of the meningohypophyseal trunk (15.9%) and ascending pharyngeal arteries (13.6%) [18].

Because there is no unified nomenclature for intracranial DAVFs, they can have several names. Most of them are based on anatomical locations of the dural layer where the fistula is situated, such as CS DAVFs and TSS DAVFs. However, some of them are named after the feeding artery, draining vein, or anatomical space, such as ethmoidal or anterior cranial fossa DAVFs, anterior condylar vein or hypoglossal canal DAVFs, and middle cranial fossa DAVFs.

Clinical presentations

The presenting symptoms vary according to the locations, complexity of angioarchitecture and presence of cortical venous reflux (CVR). A possible association between DAVFs and the pattern of venous drainage was first introduced by Houser et al. in 1972 [29]. Lasjaunias et al. reported that the clinical symptoms associated with DAVFs appear to be related to passive venous hypertension [44]. Clinical courses are usually classified by severity as follows: asymptomatic, benign and aggressive. The asymptomatic course refers to cases appearing as incidental findings. A benign course represents symptoms, such as ophthalmologic symptoms (exophthalmos, conjunctival hyperemia, eyeball pain and blurred vision), tinnitus and bruit, which can be caused by fistulous blood flow itself or extracranial symptoms due to local and mild venous hypertension. The aggressive course is characterized by pathological manifestations in the central nervous system due to venous hypertension, consisting of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and nonhemorrhagic neurologic deficits (NHNDs). ICH is the worst sequelae [76]. NHNDs include seizure, cranial nerve palsy, trigeminal neuralgia, dementia, parkinsonism, cerebellar dysfunction, motor weakness, sensory disturbance, myelopathy, aphasia, apathy, apraxia and signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, nausea, vomiting and papilledema). It is speculated that unrelenting venous reflux and cortical venous hypertension may induce venous congestion or cause fragile arterialized parenchymal veins to rupture [7,44], resulting in a limited oxygen supply to arteries, an inadequate removal of waste products [32,41], and disturbance of normal cellular metabolism [66]. In such an impaired system, CVR becomes the pivotal factor potentiating the likelihood of ICH or NHNDs [6,13,66].

Depending on the locations of DAVFs, presenting symptoms can vary. Ocular symptoms, such as ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, chemosis, retro-orbital pain, or decreased visual acuity, are mainly associated with CS DAVFs [6,12,19]. Bruit and tinnitus are commonly associated with CS, TSS and tentorial DAVFs [37]. Pulsatile tinnitus is a typical manifestation of TSS DAVFs [60], which are caused by venous turbulence in contact with the petrous bone or high shunt flow into the petrosal sinus [36]. Headaches and ICH are symptoms related to TSS, SSS, tentorial and anterior cranial fossa DAVFs [37]. As the anterior condylar vein DAVFs are located to close to the petrous bone, severe tinnitus and pulsatile bruit can appear [22]. Due to the anatomical association with the hypoglossal canal, patients with the anterior condylar vein DAVF may present with hypoglossal nerve palsy [22].

Depending on the pattern of venous drainage, patients with intracranial DAVFs with CVR are more prone to present with aggressive symptoms such as NHNDs and ICH [16,70,71]. ICH may occur in approximately 20–33% of patients with DAVFs [19,50]. SSS and anterior cranial fossa DAVFs are well known to have a high risk of ICH [11,13,44,49].

Classification

Proper classification of DAVFs allows for more accurate risk stratification and subsequently helps to make appropriate therapeutic strategies. The Djindjian and Merland classification was first suggested based on the venous drainage patterns in 1978 [21]. This classification scheme defines four types of DAVFs (type 1–4) and indicates that a higher type correlates with poor clinical manifestations. This classification is considered to be the foundation of subsequent classification schemes. This system was used in a multi-institutional analysis study about the natural course of untreated DAVFs [24], and the study showed that higher types (II-IV) predicted the likelihood of aggressive manifestations—the higher the grade of DAVFs, the higher the risk of ICH or NHNDs.

The Borden-Shucart classification was then introduced in 1995 (Table 1). This classification system is one of the most widely used systems and is used to predict a strong correlation with venous drainage patterns [6]. This classification was designed to reflect that hemodynamic variables including ‘antegrade venous drainage via sinus’ and ‘retrograde drainage into cortical vein’ correlate with poor clinical course [6]. Given this principle, it distinguishes three main types and two subtypes based on the presence of a single fistula (subtype a) or multiple fistulas in a single region (subtype b).

The Cognard classification was also introduced in 1995 [13]. The concept of ‘sinus reflux’ was first reported by Lalwani et al. in 1993 [43]. This concept was reflected on the Cognard classification scheme (Table 1). Types are categorized into types I, IIa, IIb, IIa+b, III, IV and V. The principal concepts are similar to the previously introduced classifications, but differences include the following: 1) subcategorized Borden type II into three subtypes based on the venous reflux patterns: 2) introduction of type IV with venous ectasia; and 3) type V with spinal venous drainage in which myelopathy presents as a neurological manifestation. These findings also reflect that higher types correlate with aggressive clinical manifestations such as ICH and NHNDs.

In 2009, Zipfel et al. presented a modified classification of the Cognard and Borden classification systems [82]. It emphasizes the differences in clinical courses and differentiates asymptomatic CVR from symptomatic CVR. Barrow classification was introduced based on angioarchitecture to categorize caroticocavernous fistulas as direct (Type A) or indirect (Type B, C and D) [3]. However, this system was not considered to be clinically useful [47].

Diagnosis

Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) and conventional magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can demonstrate ICH, cerebral edema, venous congestion, tortuous cortical veins and parenchymal changes [12,15,53]. CT and MR angiography allow us to identify abnormal vascular structures and to differentiate the arterial and venous phases [61]. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard imaging modality for diagnosing intracranial DAVFs. DSA is critical in detecting feeders, fistulas, and venous drainage, allowing us to proceed with further intervention when necessary. Given the above, CT and MR are mainly used as a follow-up tool and for screening. DSA is essential for confirming a diagnosis according to the locations and types of intracranial DAVFs and for subsequent treatment planning.

TREATMENT

The treatment goal is to improve clinical symptoms and signs by controlling venous hypertension. Therapeutic strategies for intracranial DAVFs are determined by multiple factors, including venous drainage pattern, natural course of the DAVFs, angiographic features and general condition of the patients. Patients with lesions presenting with no or mild symptoms and no CVR can be conservatively managed with regular follow-ups. Sometimes, a maneuver such as external manual carotid compression is reported to be effective for some DAVFs [25,35]. However, most symptomatic lesions should be considered for treatment with available modalities, including endovascular intervention, surgery, radiosurgery/radiotherapy, or a combination of these therapeutic options. Based on the literature and our database under the approval of institutional review board, we present a review of the treatment options with an emphasis on open surgery.

Endovascular intervention

Endovascular intervention is the most preferred treatment modality for most types of intracranial DAVFs [4,26,28]. The goal of treatment is complete obliteration of fistular segments, which can be achieved by interventions via the arterial or venous systems, or a combination of both approaches. Transarterial embolization (TAE) of fistular points via feeders with coils, particles and glues is an effective endovascular approach. TAE is frequently performed for TSS, SSS, foramen magnum/craniocervical junction and convexity DAVFs. Compared to transvenous embolization (TVE), the iatrogenic risk of obliterating or redirecting the normal functional venous pathway is relatively low, and the venous system can be better preserved. However, arterial access is limited in lesions with short, thin or tortuous arterial feeders. Iatrogenic occlusion of the critical arteries can cause cerebral infarction, resulting in various neurological deficits [5]. TVE involves retrograde catheterization of draining veins or sinuses, followed by deposition of coils and glues. The goal of TVE is the obliteration of the fistular segment on the venous side and disconnection of venous reflux to preserve the normal function of the venous drainage system [23]. It is a favorable treatment option for many DAVFs with multiple small arterial feeders, such as CS, TSS, SSS and anterior condylar vein DAVFs [14,46,69]. Nonetheless, a blockage in the normal venous drainage system can rarely cause devastating problems, such as additional venous hypertension and hemorrhage (Fig. 1) [39,81].

Axial CT images after TVE for the intracranial DAVF. Two hours after TVE, the patient complained of severe headache (A). After three hours, the patient lost consciousness due to ICH, intraventricular hemorrhage, and hydrocephalus (B). Twelve hours later, brain swelling and hemorrhage in the deep venous system were observed on brain CT, implying a compromise of the deep venous system after TVE (C). CT, computed tomography; TVE, transvenous embolization; DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage

From 2003 to 2021 in our institution, a total of 431 endovascular procedures were performed in 382 patients with intracranial DAVFs arising in the CS, TSS, SSS, torcular herophili, tentorium, straight sinus, superior petrosal sinus, jugular bulb, anterior condylar vein, foramen magnum/craniocervical junction, convexity, vein of Galen, and anterior and middle cranial fossa. Among the 431 endovascular interventions performed, interventions for CS-DAVFs were the most common (41.5%), followed by interventions for TSS lesions (25.8%).

Radiosurgery

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is known as a noninvasive, low-risk treatment modality that is often reserved for some DAVFs, in which complete obliteration of residual nidus cannot be achieved with endovascular and/or surgical management. It is important to note that complete obliteration of the DAVFs following SRS takes 1-3 years, so this therapy modality is indicated for low-grade DAVFs, not for aggressive DAVFs with a high risk of ICH and NHNDs [10]. Favorable outcomes of complete obliteration have been reported [10,74]. Moreover, some studies have been conducted to evaluate SRS as a primary treatment option for selected cases of DAVFs, demonstrating good outcomes [2,63,80]. Its efficacy should be evaluated with more and larger studies. Radiotherapy is rarely attempted in some institutions; however, there have been no formal reports about the results.

Sixteen patients underwent radiosurgery as an adjunctive modality for residual lesions between 2004 and 2017 [72]. A relatively small group of patients underwent radiosurgery, and their angiographic and clinical outcomes were excellent—complete obliteration was achieved in 10 (62.5%) patients and 15 patients showed clinical improvements or no change (94%).

Surgery

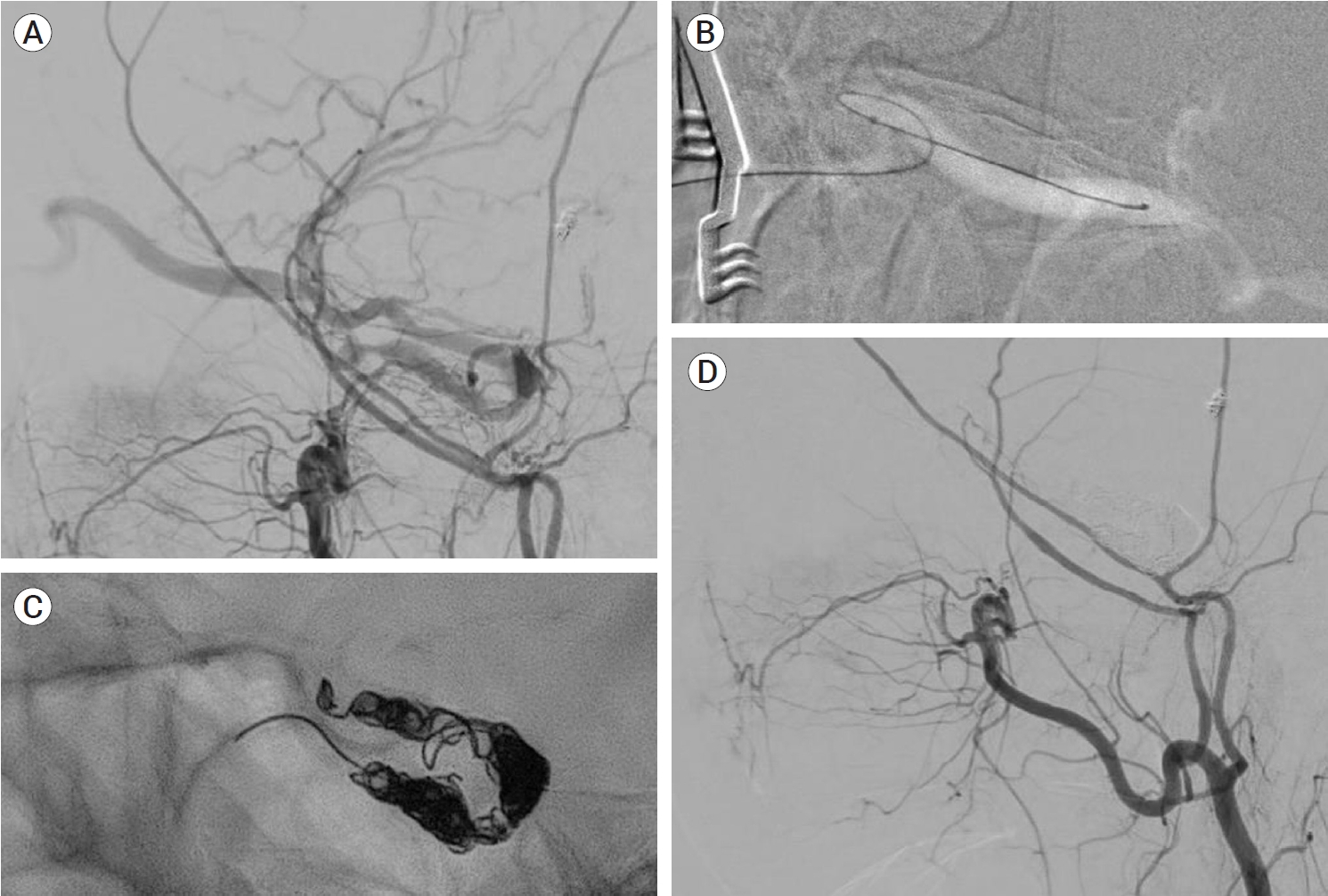

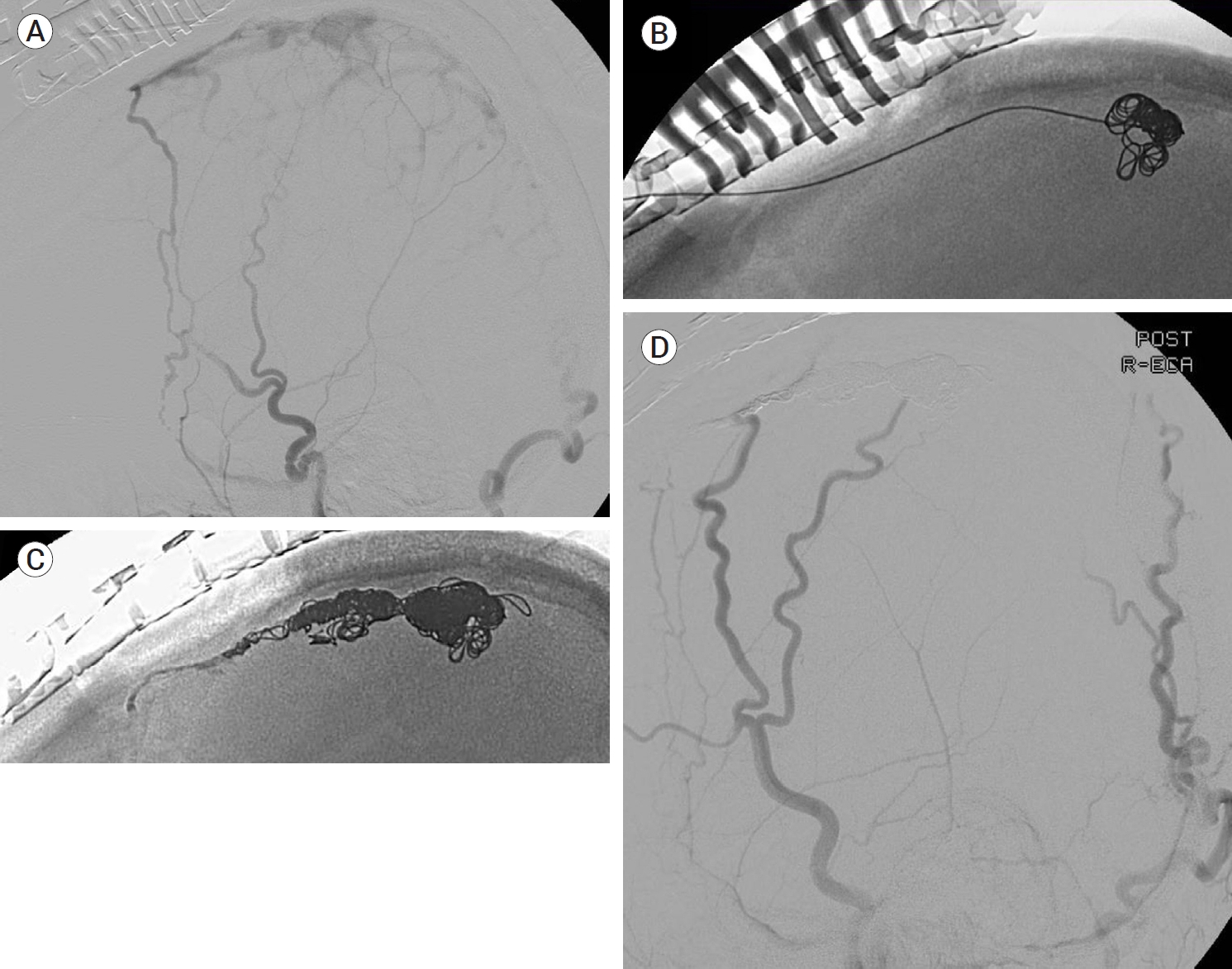

At present, there are three surgical strategies available for the management of intracranial DAVFs. The first strategy comprises creating an access route for further endovascular intervention. The next strategy involves disconnecting the fistular point. The third strategy includes total resection of nonfunctioning or isolated segments of the sinuses harboring the fistulas. The combination of surgical and endovascular approaches is the most common approach in open surgery for the treatment of intracranial DAVFs. Conventional endovascular access routes are often unavailable in a subset of complicated vascular architecture so alternative approaches are needed. In such cases, open surgical exposure is used to achieve access to the fistulous points for the endovascular intervention. For instance, TVE via the inferior and superior petrosal sinuses and facial vein is usually performed for the treatment of CS DAVFs [28,68,81]. Even in cases with an occluded inferior petrosal sinus (IPS), TVE can be performed [17,34,68]. In such cases for which the endovascular procedure is unsuitable, transorbital access to the cavernous sinus can be achieved via a direct puncture of the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins following surgical exposure (Fig. 2) [62,67]. Alternatively, transcranial puncture of the superficial middle cerebral vein can also offer be considered a route to the cavernous sinus for further endovascular procedures [9,19]. Treatment of SSS DAVFs is sometimes challenging due to the fine and tortuous multiple arterial feeders, such as the middle meningeal arteries. Additionally, for such cases, surgical exposure provides a route to overcome arterial tortuosity (Fig. 3) [59]. Specific lesions located in the TSS and anterior condylar vein DAVFs are reported to be treated with the help of direct surgical puncture [54,61].

An ECA angiogram showing a Cognard type IIa+b CS DAVF. TVE through the inferior petrosal sinus was infeasible (A). Microcatheter navigation through the ophthalmic vein and TVE were successful via a surgical direct puncture (B and C). A postprocedural angiogram showed a complete occlusion (D). ECA, external carotid arteries; CS, cavernous sinus; DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; TVE, transvenous embolization

An ECA angiogram showed an isolated Cognard type III SSS DAVF (A). Exposing the SSS via a craniotomy, a direct puncture and following TVE were successfully performed (B and C). A postinterventional angiogram showed no remaining shunt (D). ECA, external carotid arteries; SSS, superior sagittal sinus; DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; TVE, transvenous embolization

Surgery alone is generally indicated only for selected cases of intracranial DAVFs for which routes for TAE or TVE are inaccessible. In selecting an open surgery, however, there are some considerations: 1) whether the CVR is global or focal because diffuse and uncontrollable venous bleeding can occur in cases with global CVR; and 2) disconnection of the fistular points is enough, and extensive extirpation of dilated draining veins should be avoided, which compromises normal venous drainage and leads to subsequent brain damage [10,27]. The intracranial DAVFs suitable for surgical treatment include lesions involving convexity [75], foramen magnum/craniocervical junction [65] and anterior cranial fossa DAVFs [33]. In these regions, arterial feeders are usually short, thin, and tortuous; and creating a venous access is generally impossible. Regarding the anterior cranial fossa or ethmoidal DAVFs, no dural sinus exists on the anterior cranial fossa, and venous flow often drains often via frontal cortical veins into the superior sagittal sinus [1], leading to a high risk of ICH [31]. Due to the risk for inadvertent embolization of the central retinal artery and small calibre of ethmoidal arteries, open surgery is suitable as the first line of treatment [45]. The nonfunctioning and isolated sinuses involved in intracranial DAVFs can be surgically resected, which is called skeletonization. Borden et al. suggested that skeletonization is indicated for the treatment of type Ib DAVF [6]. All the connections between feeders and a draining sinus can be sequentially disconnected, followed by removal of a nonfunctioning sinus harboring fistulas.

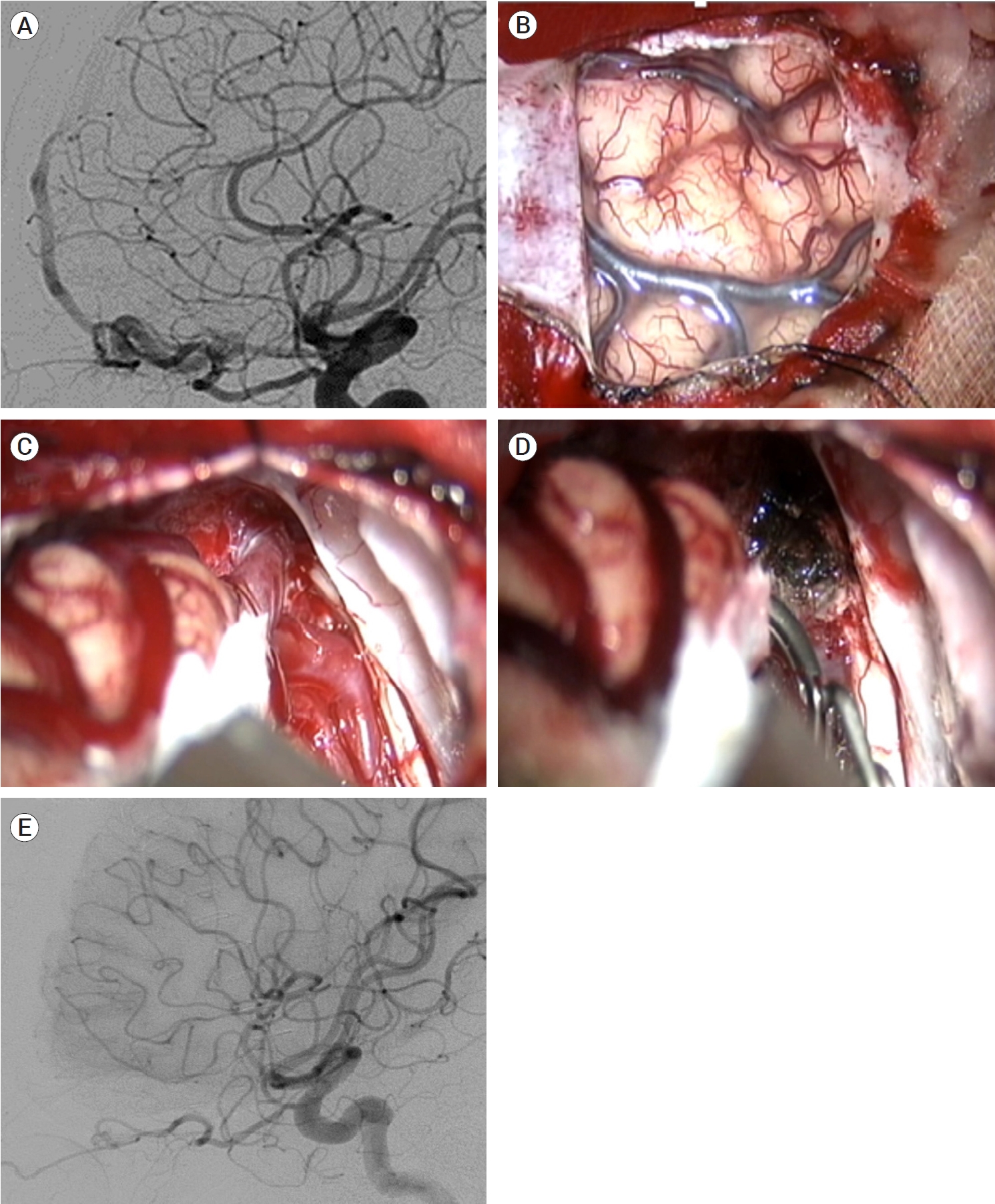

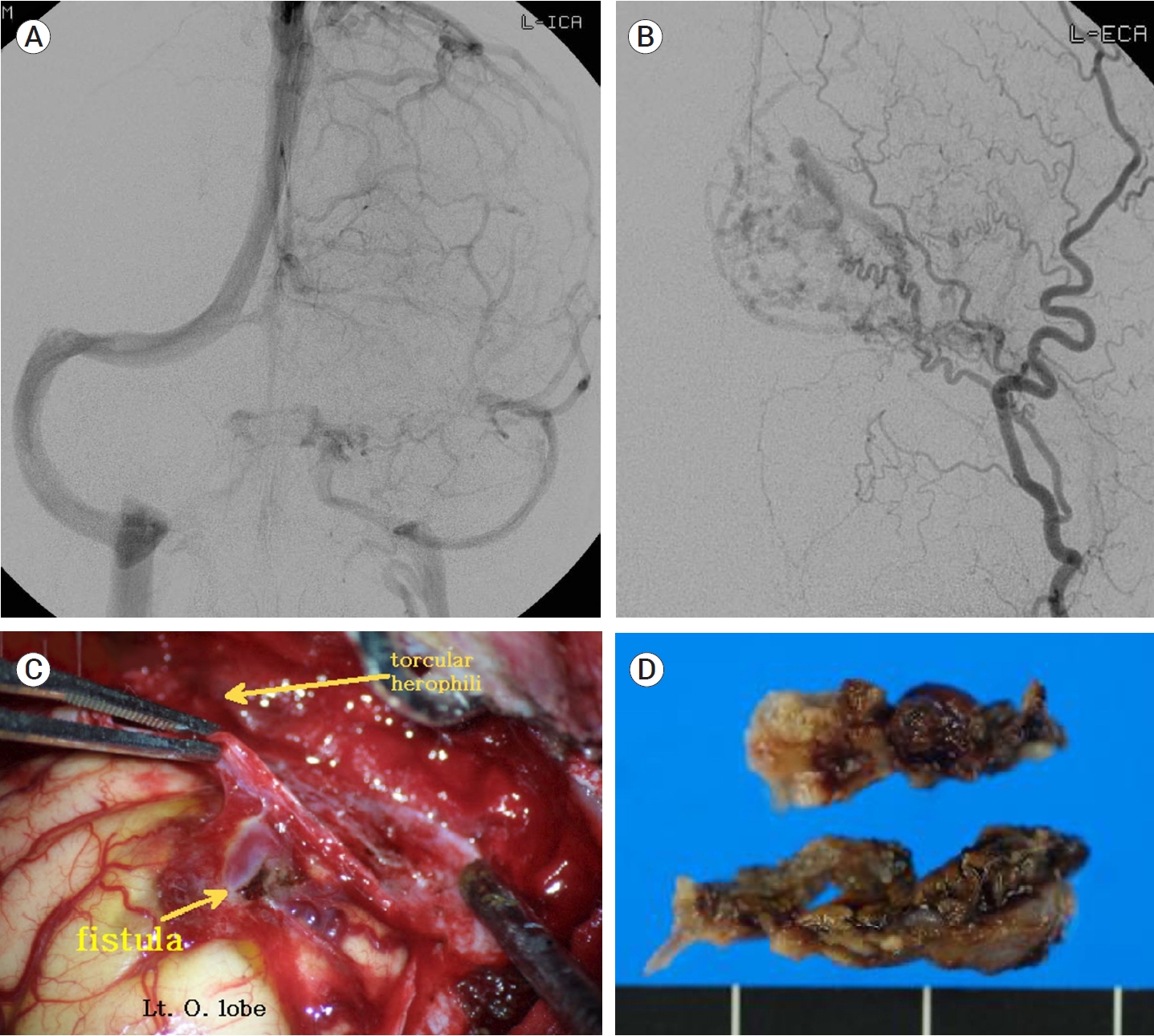

Between 2003 and 2021, 22 patients with intracranial DAVFs underwent surgical treatment, except for the patients treated with surgical exposure and endovascular obliteration. Fifteen cases of anterior cranial fossa DAVFs were surgically treated with fistula obliteration. Frontobasal craniotomy has been one of the most widely performed procedures because it provides the shortest distance to the fistula and a relatively wide working space [33]. However, a wide skin incision, excessive bone exposure and high risk of complications such as infection, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, and formation of mucocele are disadvantages of this approach [33]. Recently, less invasive surgical approaches, such as a minipterional approach, a supra-orbital craniotomy and an anterior interhemispheric approach, have been attempted [20,51,52,58,79]. We recently introduced a novel technique of a unilateral small high frontal approach for direct exposure of the fistula (Fig. 4) [33]. Following a unilateral curvilinear skin incision, above the frontal sinus, a unilateral small high frontal craniotomy was performed. As the dura is opened, the frontal lobe sinks down, as cerebrospinal fluid is drained and the ipsilateral frontobasal area is exposed. In this approach, the working distance is shorter than that of the anterior interhemispheric approach, and it is less destructive than the frontobasal approach. In two cases of transverse sinus (TS) DAVFs, skeletonization of the involved dural sinus was performed (Fig. 5). For one patient with an SSS DAVF, fistular disconnection after partial embolization was performed (Fig. 6). In a case of middle cranial fossa DAVF, we clipped the fistula after partial embolization. Fistulas of the convexity DAVFs were surgically obliterated.

Preoperative ICA angiography showing a right ethmoidal DAVF (A). Opening the dura at the right high frontal lobe, the target fistula was identified after cerebrospinal fluid drainage and frontal retraction (B and C). The fistulas were easily coagulated and cut (D). Postoperative ICA angiography showed complete obliteration of the fistulas (E). Reprinted from Jang et al.(2019), with permission from Elsevier[33]. ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; ICA, internal carotid arteries

An occluded transverse sinus (TS) DAVF fed by left ECA arteries was identified on left anteroposterior ICA angiogram (A) and ECA angiogram (B). Small feeders were coagulated and cut (C), and occluded left TS was resected (D). DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; ECA, external carotid arteries; ICA, internal carotid arteries

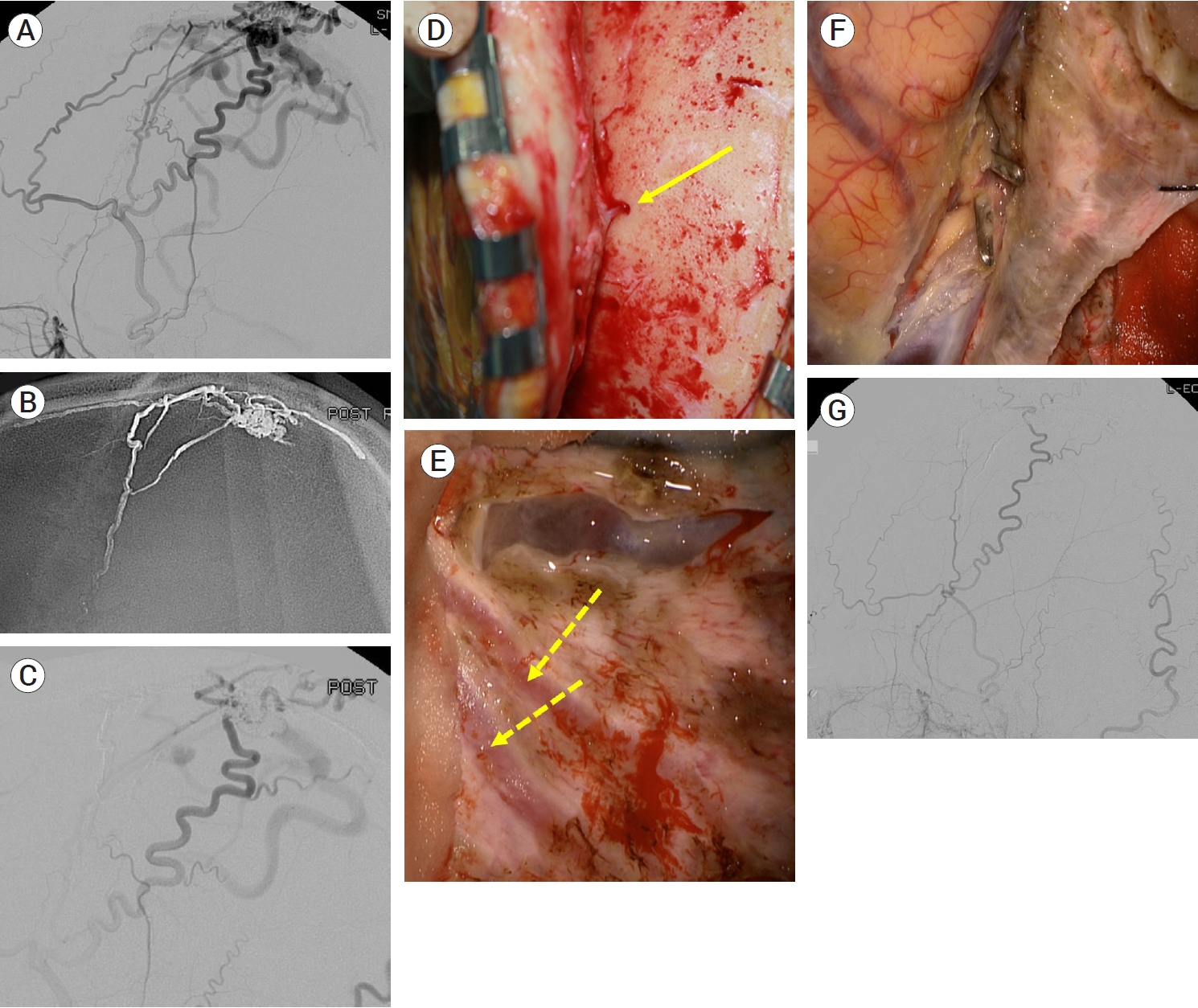

A Cognard type IIa+b SSS DVAF fed by branches of superficial temporal, occipital and middle meningeal arteries was identified on an ECA angiogram (A). TAE with Onyx® via the middle meningeal artery was partially performed (B and C). Surgical obliteration was planned for remnant lesion. Small transosseous feeders from superficial temporal artery (arrow) were coagulated and cut during scalp reflection (D). After craniotomy, remnant feeders from middle meningeal arteries (dotted arrows) were coagulated and cut (E). A fistulous segment of a draining vein beside the SSS was coagulated and cut (F). A postoperative ECA angiogram showed no remaining fistulas (G). SSS, superior sagittal sinus; DAVF, dural arteriovenous fistulas; ECA, external carotid arteries; TAE, transarterial embolization

CONCLUSIONS

Intracranial DAVFs are rare, acquired lesions characterized by abnormal shunting at the dural layers between the arteries and the venous system. Most intracranial DAVFs with no CVR and tolerable symptoms are suitable for conservative management. Moreover, aggressive DAVFs with CVR should be promptly treated because they carry a high risk of ICH and NHNDs. Endovascular intervention is the main therapeutic modality. Radiosurgery and open surgery are reserved for a few specific cases of DAVFs. Although radiosurgery and radiation therapy are adjunctively performed, indications for radiation treatment are expected to be extended. Indications for surgical treatment of intracranial DAVFs usually include anterior cranial fossa DAVFs, DAVFs with nonfunctioning and isolated sinuses, convexity lesions and lesions with residual fistulas after endovascular intervention. However, a surgical armamentarium should be prepared because the surgical role in improving the clinical outcomes of patients with specific intracranial DAVFs can be critical.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund (the Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2020-KD000137).

Notes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.