Coil embolization and recurrence of ruptured aneurysm originating from hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery

Article information

Abstract

Hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery (AchA) is an extremely rare congenital vascular variant that can be mistaken for other cerebral arteries. This case report presents a 38-year-old man who presented with a severe sudden-onset headache and was diagnosed with a ruptured aneurysm originating from a hyperplastic AchA. The aneurysm was successfully treated with coil embolization, but recurrence was detected after eight months, leading to additional surgical intervention. The discussion highlights the classification of hyperplastic AchA and emphasizes the importance of recognizing this anatomical variant to avoid complications during treatment. This case report underscores the need for awareness and understanding of hyperplastic AchA in the management of cerebral aneurysms.

INTRODUCTION

Hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery (AchA) is an extremely rare congenital vascular variant, first described in 1907 [2] and incidence reported between 1.8-2.3% [11,28]. Hyperplastic-AchA (H-AchA) is occasionally confused as ‘duplicated posterior cerebral artery (PCA)’ or ‘accessary PCA’ and associated with ‘fetal type PCA’ [26]. As H-AchA has both choroidal branches and communicating functions and it supplies a broader area that is usually served by the PCA compared to the normal AchA, this variant is often misdiagnosed as a duplicated or fetal type PCA.

CASE DESCRIPTION

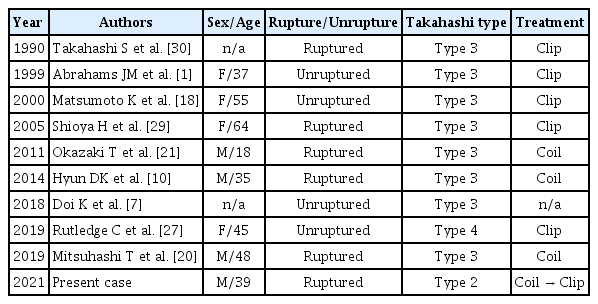

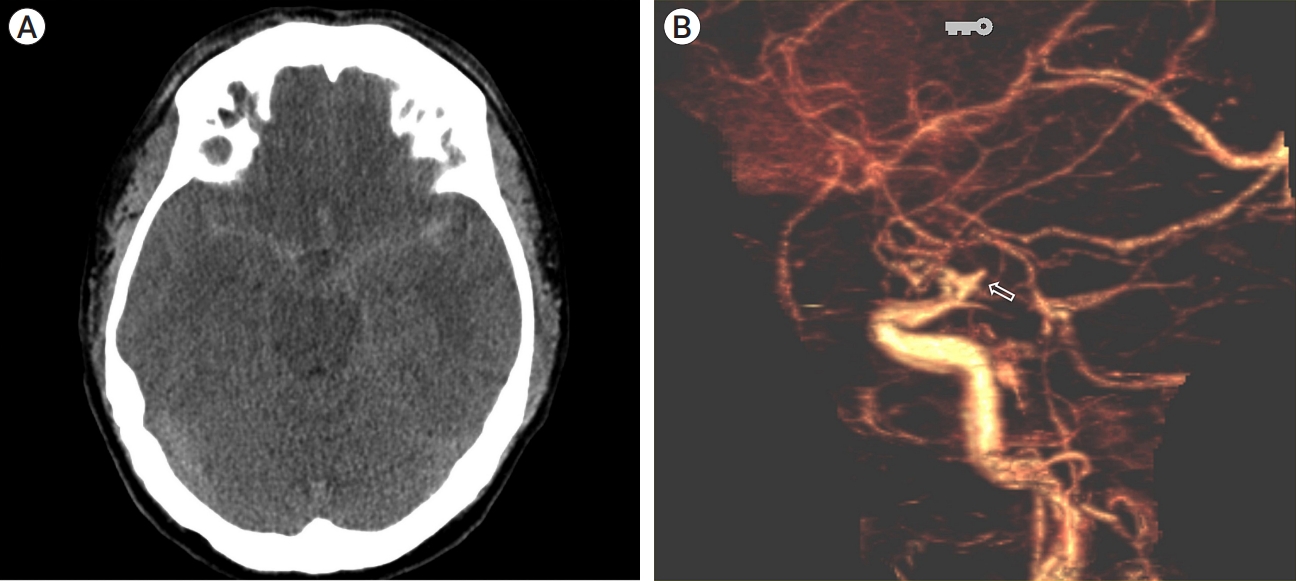

A 38-year-old man presented with a severe sudden-onset headache and had no significant previous or familial medical history. Initial non-contrast computed tomography (CT) revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the bilateral Sylvian fissure, peri-mesencephalic region, and basal cisterns (Fig. 1A). Subsequent CT angiography showed a suspicious aneurysm protruding superiorly from the left distal internal carotid artery (ICA) (Fig. 1B). Transfemoral cerebral angiography (TFCA) demonstrated that the aneurysm originated from the distal ICA. Initially, the origin of the aneurysm was considered to be a duplicated Posterior communicating artery (Pcom) or accessory PCA, but its proximal course followed the usual path of the typical cisternal segment of the AchA. Left vertebral angiograms (Alcock test) confirmed that the aneurysm originated more distally in the ICA, beyond the origin of the Pcom (Fig. 2A, B), and was definitively identified as an H-AchA aneurysm. The diameter of the H-AchA was even larger than that of the Pcom and had a lengthy course, extending distally to cover the posterior temporal area.

(A) Brain computed tomography (CT) reveals subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) within the bilateral sylvian fissure, perimesencephalic region, and basal cisterns. (B) CT angiography shows an aneurysm protruding superiorly from the left distal internal carotid artery (ICA) (open arrow).

(A) Vertebral angiography with the Alcock test demonstrates a normal posterior communicating artery (Pcom) (black arrow). The aneurysm (open arrow) originates from the anomalous hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery (H-AchA) (white arrow), and some anomalous temporal branches are observed distally (open arrowhead). The posterior cerebral artery (PCA) follows its typical course, and the distal uncal branch is observed normally (white arrowhead). (B) The 3D rotation view shows the aneurysm (open arrow) originating from the H-AchA (white arrow), along with the distal normal uncal branch of the PCA (white arrowhead). Additionally, some anomalous temporal branches from the H-AchA are observed distally (open arrowhead).

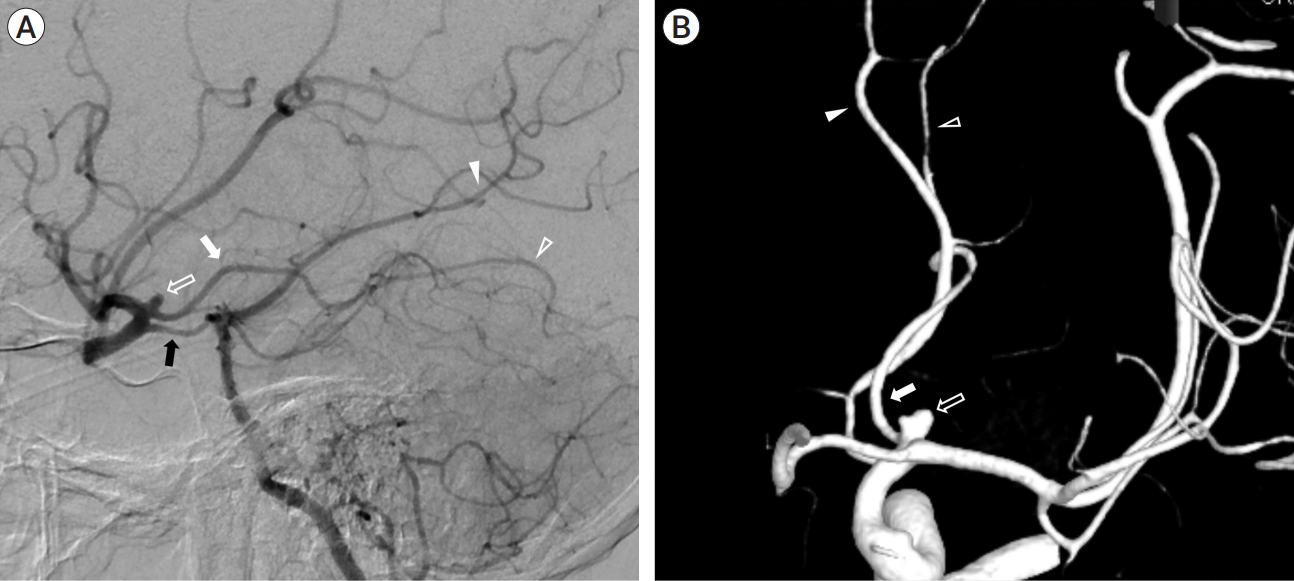

The aneurysm had a daughter sac and measured approximately 3.1 mm in diameter and it was treated with simple coil embolization. Under general anesthesia, through the right femoral artery, 6-Fr Shuttle and Sofia intermediate catheter were introduced into the left ICA. Then we used an Excelsior SL-10 microcatheter (Stryker Neurovascular, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) to navigate into the aneurysm sac and 2 detachable coils (Micrusframe S 3×5.4, Target nano 1.5×2, total coil length 7.4 cm) were filled into the sac. Immediate postprocedural angiograms showed near complete occlusion (Fig. 3A) and the packing density was about 24%. We tried additional coil (target nana 1×1) to improve packing density but failed. The patency of the fetal-type PCA and the hyperplastic AchA were preserved. The patient recovered well and was discharged after a few days without any significant events.

(A) The aneurysm was treated with simple coil embolization (white arrow). (B) After 8 months, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) reveals the recurrence of the coiled aneurysm (open arrowhead). (C) Transfemoral cerebral angiography (TFCA) confirmed the recurrence of the aneurysm with coil compaction (black arrow). (D) Recurred aneurysm (black arrowhead) is seen between ICA (open arrow) and H-AchA (white arrow). Finally, surgical clipping was performed at the recurrent aneurysm. ICA, internal carotid artery; H-AchA, hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery

However, during regular follow-up observation, aneurysmal recurrence was detected on the magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of pointwise encoding time reduction with radical acquisition (PETRA) sequence after eight months (Fig. 3B). TFCA confirmed the recurrence of the aneurysmal neck with coil compaction (Fig. 3C), and the patient ultimately underwent additional clipping surgery (Fig. 3D).

DISCUSSION

AchA aneurysms represent 2-4% of all intracranial aneurysms [24] and aneurysms associated with H-AchA have higher incidence [30] of 4-17% compared to typical AchA aneurysms. In a domestic study, out of 90 AchA aneurysms, 6 aneurysms (7%) were reported to be associated with H-AchA [13].

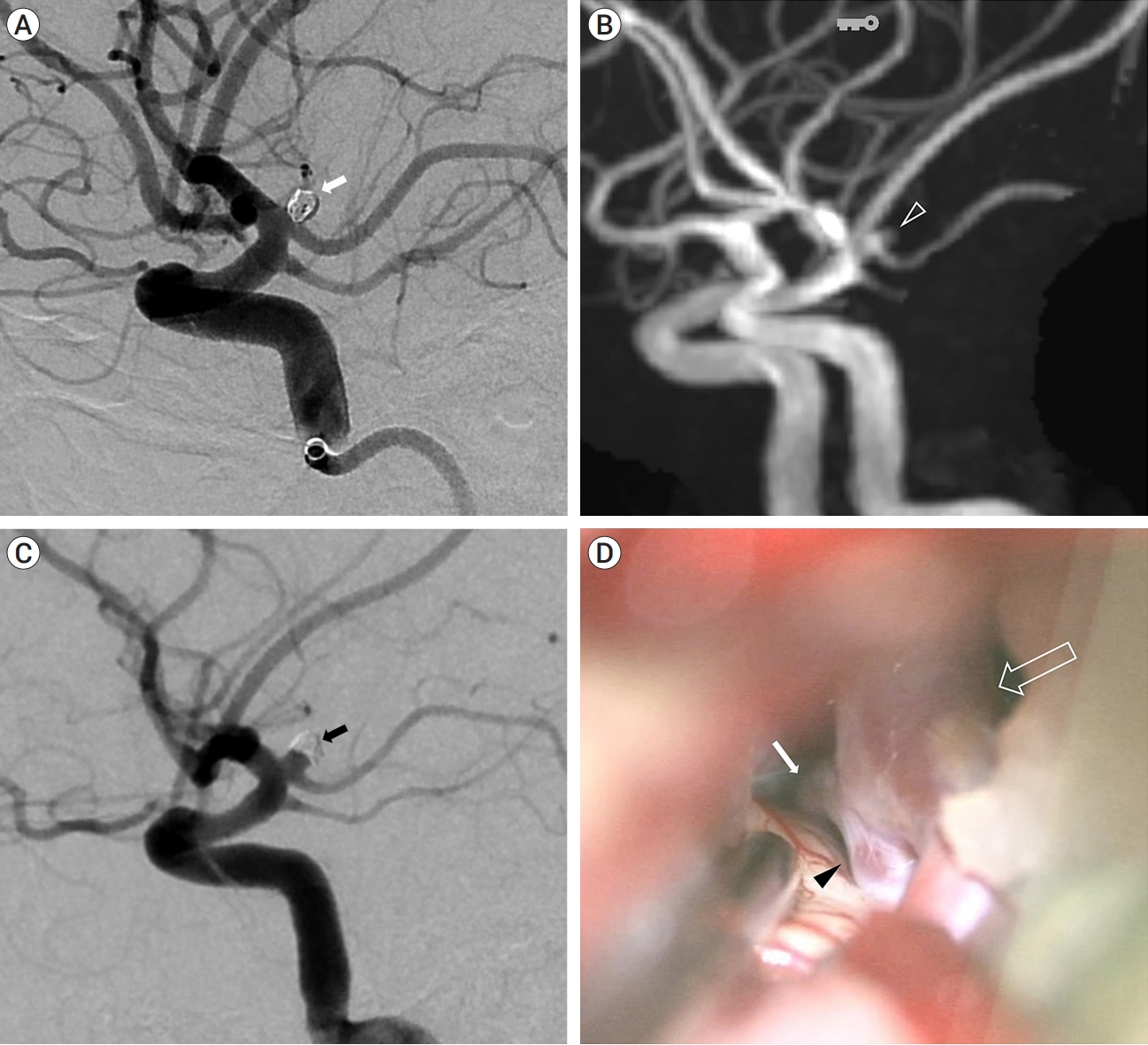

H-AchA was first classified into four types by Takahashi in 1990 based on the location of the remnant anastomosis between AchA and Pcom with PCA [30]. These types include hypertrophic uncal branch (type 1), anomalous temporal artery (type 2), anomalous occipito-parietal artery (type 3), and anomalous temporo-occipito-parietal artery (type 4). The patient in our case corresponds to type 2 of this classification, where H-AchA supplies some posterior temporal branches while the PCA proper gives rise to its own uncal branch. In our case, CT angiography revealed an additional artery arising from the communicating segment of the ICA, distal to the origin of the Pcom, which coursed postero-laterally. TFCA confirmed it as H-AchA and demonstrated its branches supplying the temporal areas along with the normal uncal branch of the PCA (Fig. 2).

H-AchA is referred to as ‘duplication of PCA’ or ‘true fetal PCA’, because it is believed to have similar developmental origins [9]. These terms highlight the resemblance and shared underlying causes of these vascular anomalies. Around the choroidal stage of fetal development (approximately at 5 weeks), the AchA initially supplies the territory of the PCA. As the brain volume increases and the posterior circulation develops, the normal pattern involves a reduction in blood supply from the AchA, leading to diminished hemispheric involvement of the AchA. However, in some cases, an unusual vascular regression occurs, resulting in a variant where the AchA continues to supply the posterior circulation from the anterior circulation and maintains its communicating function.

There are several cases about H-AchA aneurysm (Table 1). Present case is the first report of ruptured aneurysm from type 2 H-AchA and early recurrence of a ruptured H-AchA aneurysm after treatment. Previous studies have demonstrated that predisposing factors for recurrent coiled aneurysms include large side, widenecked, and ruptured [12,15]. Specially, large Pcom or fetaltype Pcom has been reported to be correlated with recurrence after coil embolization [5,14,16]. Considering that the location of the aneurysm in this case was almost identical to that of the Pcom, the aneurysm was ruptured, had a wide neck, and was associated with a large H-AchA, indicating a high risk of recurrence after coil embolization [3,4,16,23]. Further, the recurrence was somewhat earlier than usual aneurysms, and the immediate post-coil angiogram was close to Raymond class I [17,25], but the packing density was relatively low as 24%, which might have attributed to early recurrence [8,19,31]. When coiling a ruptured aneurysm in the ICA, considering early recurrence, a short term follow-up within 6 months would be recommended [6,22,23].

CONCLUSIONS

Although hyperplasia of AchA is a rare variant, it is associated with a relatively higher incidence of aneurysm formation compared to the original AchA. Given that the thromboembolic event (including sacrifice) of an H-AchA aneurysm can lead to more severe complications than in the case of the Pcom, it is important to recognize the anatomical variant of H-AchA. The recognition of this anatomical variant is crucial because the treatment-related complications of H-AchA aneurysms can result in severe and unexpected consequences [10]. Therefore, awareness of this variant is essential for providing appropriate and targeted care to patients.

Notes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.