Iatrogenic mixed pial and dural arteriovenous fistula after pterional approach for surgical clipping of aneurysm: A case report

Article information

Abstract

Craniotomy is known as a cause of iatrogenic dural cerebral arteriovenous fistula (AVF). However, mixed pial and dural AVFs after craniotomy are extremely rare and require accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment due to their aggressiveness. We present a case of an iatrogenic mixed pial and dural AVF diagnosed 2 years after pterional craniotomy for surgical clipping of a ruptured anterior choroidal aneurysm. The lesion was successfully treated using single endovascular procedure of transvenous coil embolization through the engorged vein of Labbe and the superficial middle cerebral vein. The possibility of the AVF formation after the pterional approach should always be kept in mind because it usually occurs at the middle cranial fossa, which frequently has an aggressive nature owing to direct cortical venous or leptomeningeal drainage patterns. This complication is believed to be caused by angiogenetic conditions due to coagulation, retraction, and microinjuries of the perisylvian vessels, and can be prevented by performing careful sylvian dissection according to patient-specific perisylvian venous anatomy.

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is a rare heterogeneous vascular disease that has various morphological and hemodynamical differences of draining veins and feeding arteries among cases [7,10,18,22,25]. Dural AVFs are defined as AVFs fed by branches of the dural arteries and are lesions occasionally associated with cerebral venous thrombosis, inflammation, trauma, and craniotomy. On the other hand, pial AVFs consist of feeders from the pial arteries, which are related to congenital and various conditions, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and neurofibromatosis type 1 [2,6,7,18]. Due to the differences in etiology, mixed dural and pial AVF is an extremely rare condition, which has been infrequently reported worldwide [6].

Some reports have described iatrogenic AVF after various craniotomies, and intraoperative microinjuries, venous thrombosis, and sinus occlusions are known pathophysiologies [1,4-6,9,10,14,20,25,28,29]. However, AVF formation after aneurysm surgery through the pterional approach is infrequently reported despite the large number of the surgeries worldwide [4,6,25]. Although the disease may result in fatal neurological outcomes due to venous hypertension and intracranial hemorrhage, it may be overlooked or missed if asymptomatic, as iatrogenic AVF is not a well-known complication of clipping surgery.

We present an extremely rare case of mixed pial and dural AVF at the middle cranial fossa after a conventional pterional approach for surgical clipping of a ruptured anterior choroidal artery aneurysm which was successfully treated with endovascular transvenous embolization through the engorged vein of Labbe.

CASE DESCRIPTION

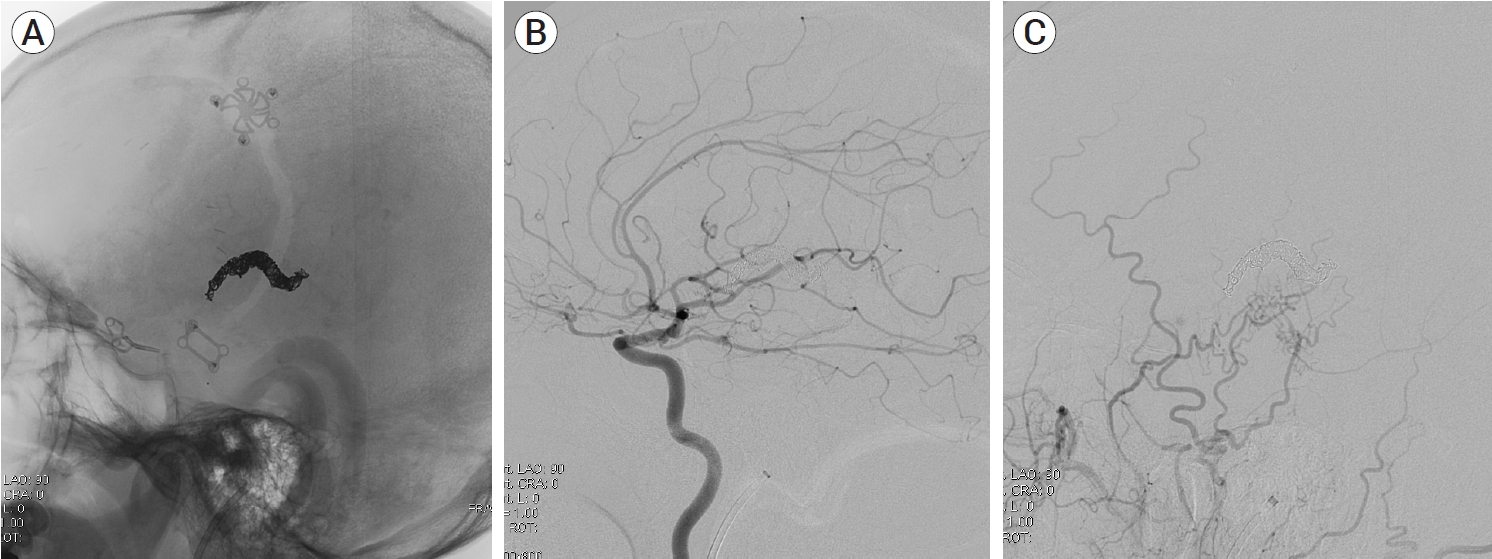

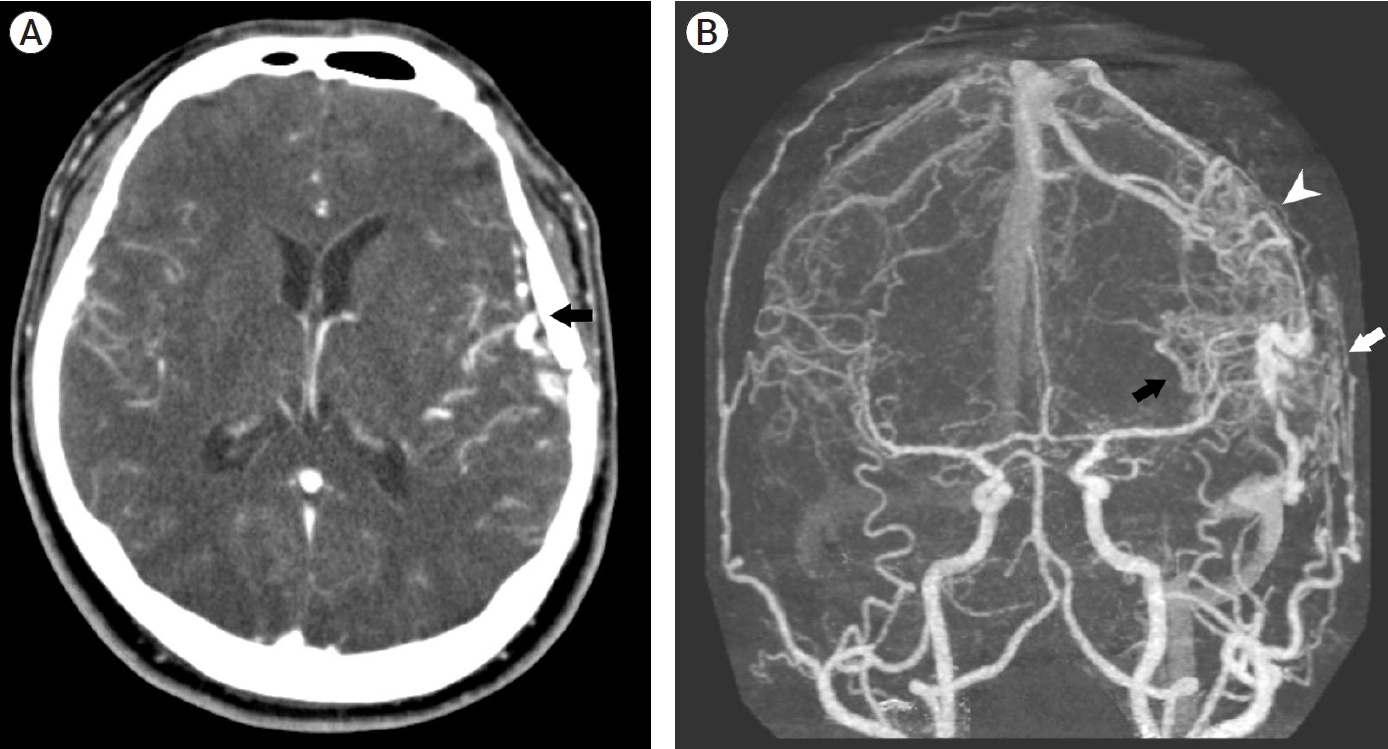

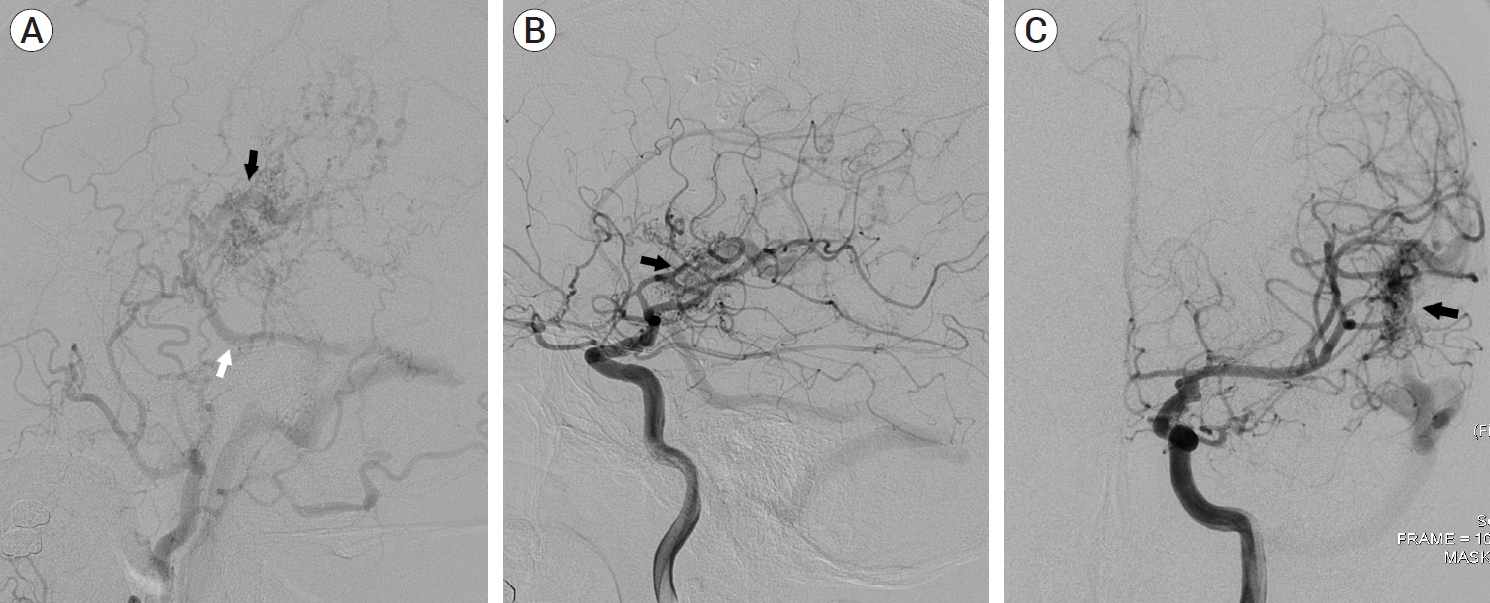

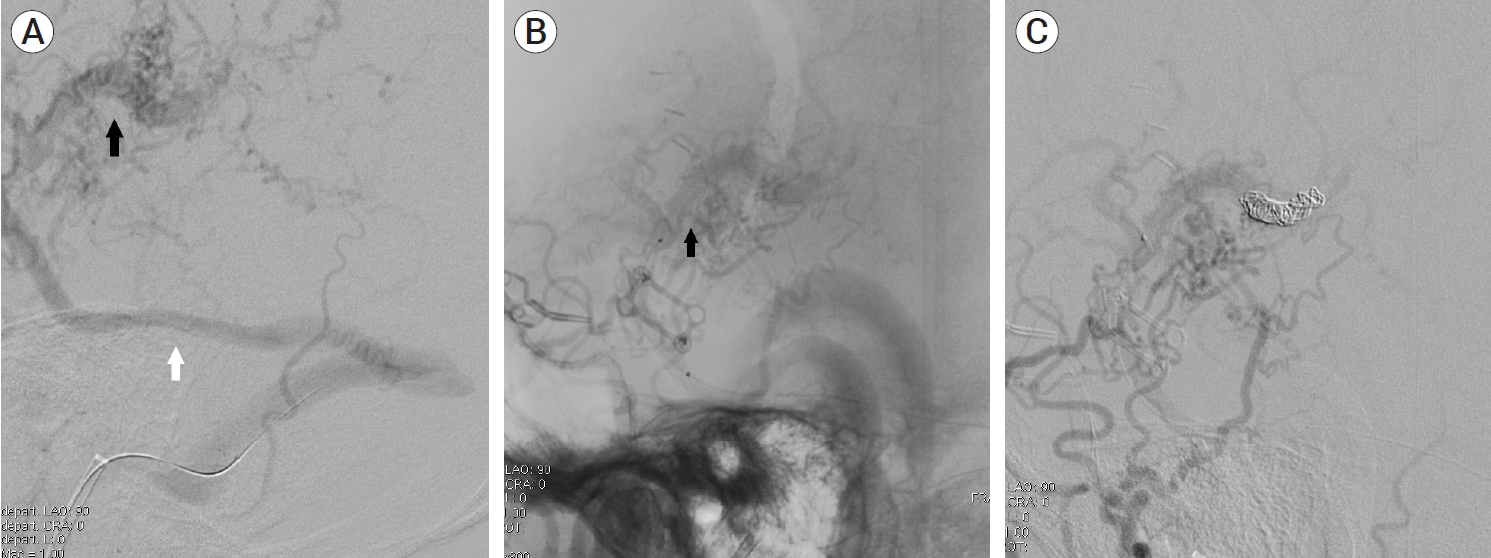

A 39-year-old man visited the neurosurgery department and presented with a left-sided pulsatile headache. The patient had a history of surgical clipping for a ruptured left anterior choroidal artery aneurysm using a conventional pterional approach 2 years previously. Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed engorged tortuous cortical vessels near the previous craniotomy site and sylvian fissure, indicating a suspicious AVF which had not been detected on CT conducted 2-years before presentation (Fig. 1). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed for treatment planning, and external carotid angiography demonstrated a dural AVF fed by the branches of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) and superficial temporal artery (STA), draining directly into the engorged superficial middle cerebral vein (SMCV), vein of Labbe, and sigmoid sinus (Fig. 2A). Ectatic changes in the draining veins and cortical venous reflux were observed. Ipsilateral internal carotid artery angiography revealed additional multiple feeders arising from the middle cerebral artery (MCA), suggesting a mixed pial and dural AVF (Fig. 2B, C). Due to the difficulty of the transarterial approach through multiple small feeding arteries, transvenous coil embolization was performed via the sigmoid sinus and enlarged vein of Labbe (Fig. 3). Complete obliteration of the fistula was achieved, confirmed by postoperative DSA (Fig. 4), and the patient was discharged with no neurological complications.

(A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showing venous ectasias beneath the previous left craniotomy site (black arrow). (B) Three-dimensionally reconstructed CT angiography demonstrating suspicious dual arteriovenous fistula with multiple feeders from pial arteries (black arrow) and dural arteries (white arrow). Cortical venous reflux and venous hypertension is suspected (arrowhead).

(A) Left external carotid artery angiography demonstrating multiple feeders from the middle meningeal artery and superficial temporal artery. Drainage pattern to engorge the superficial middle cerebral vein (black arrow) and vein of Labbe (white arrow) is noted. (B, C) Left internal carotid artery angiography showing additional multiple pial arterial feeders arising from the middle cerebral artery (black arrow).

(A, B) Intraoperative angiography showing microcatheter advancement to the fistulous point (black arrow), superficial middle cerebral vein (SMCV), via sigmoid sinus and vein of Labbe (white arrow). (C) Coil embolization of SMCV was performed.

DISCUSSION

Development of an acquired dural AVF, and the associated pathophysiology, has two main reported hypotheses. The first is related to progressive venous sinus thrombosis and the opening of microvascular connections. The sinus thrombosis or occlusion occurring during posterior fossa and midline craniotomy surgery may therefore trigger iatrogenic dural AVF [20,22,28,29]. The second mechanism of dural AVF development is the expression of angiogenesis growth factors due to a neovascularization-promoting environment such as inflammation, ischemia, hemorrhage, and traumatic vessel injuries [3,6,16]. Craniotomy is the most common cause of iatrogenic dural AVF formation, but the mechanism of the pathology remains unknown; however, the leading hypothesis is that inflammatory reactions and the repair processes of intraoperative injuries are responsible for the pathophysiology, which is related to second hypothesis of dural AVF formation explained above [4-6,9,13,14]. Many reports have proven that angioneogenesis is caused by the release of vascular endothelial growth factor after traumatic vessel injuries and parenchymal injury, and this explains and supports the mechanism of AVF formation after vascular microinjury during craniotomy and brain dissections [3,6,16]. Incomplete dural closure also may be a cause of abnormal epidural and intradural anastomosis and angiogenetic environment.

Unlike dural AVFs, which are mostly acquired lesions consisting of dural arterial feeders, pial AVFs are fed by pial arterial branches or cortical arteries and are generally associated with younger patients and congenital diseases such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Rendu-OilerWeber disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1 [2,6,7,18,19,21]. Iatrogenic pial AVF is a rarer condition, and there have been some reports of acquired pial AVFs after numerous procedures such as craniotomy and radiosurgery, or repeated trauma [2,6,18]. Pial AVF requires prompt treatment because the high flow of the fistula makes it more aggressive than dural AVFs and more often creates venous ectasia [2,7,15,26]. Furthermore, they usually have multiple small arterial feeders from pial or cortical arteries, which complicates treatment [7,26].

Because of the difference in etiology between pial AVF and dural AVF, mixed pial and dural AVF is very rarely reported. To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first of a directly diagnosed mixed pial and dural AVF after craniotomy that has demonstrated prominent pial arterial feeders from the MCA and dural arterial feeders from the MMA and STA. The drainage pattern of the AVF via the SMCV and the engorged anastomotic vein of Labbe enabled us to approach transvenously via the sigmoid sinus and perform successful coil embolization of the fistulous points. The transarterial approach and open surgery were not attempted because the fistula had multiple small tortuous pial arterial feeders arising from the MCA branches and dural arterial feeders arising from the MMA and STA.

Doi et al. (2019) reported a late diagnosed mixed pial and dural AVF after craniotomy [6]. Postoperative DSA after open surgery for an iatrogenic dural AVF caused by surgical clipping of an MCA aneurysm showed complete obliteration of the dural feeders. However, it also revealed remnant fistula and new feeders from multiple pial arterial branches near a previously clipped aneurysm, indicating the AVF was a mixed pial and dural AVF. Preoperative DSA showed only dural arterial feeders from the MMA and did not show feeders from the pial arteries, which misled the authors to consider it a dural AVF. The high flow of dural arterial feeders may have blocked the flow of the small pial arterial feeders preoperatively. Additional gamma knife surgery was performed for obliteration of the remnant fistula [6].

Although a greater number of patients undergo aneurysm surgery worldwide through the pterional approach than other craniotomies, few reports of iatrogenic AVF following the procedure have been published [4,6,25]. Sylvian fissure dissection is performed during most surgeries for anterior circulation artery aneurysms; therefore, manipulation, coagulation, and retraction of perisylvian vessels may be potential causes of AVF formation. Consequently, the surgeon should take care, as much as is possible, that such vessels are not damaged during sylvian fissure dissection [17]. The SMCV can interfere with the pterional approach; therefore, good knowledge of the various anatomical relationships between the SMCV and the frontotemporal lobe is required. According to Yasargil (1984), vascular neurosurgeons tend to dissect between the SMCV and frontal lobe during the transsylvian approach [27]. However, this may lead to unnecessary manipulation and coagulation of the fronto-sylvian bridging veins [11,12,17]. Imada et al. (2021, 2019) used cadaver dissection to understand and introduce morphological patterns and classification of the SMCV based on its relationship with fronto-sylvian and temporo-sylvian veins, which is a useful reference during surgery [11,12]. Unnecessary damage can be prevented by performing sylvian dissection according to the patient’s specific SMCV anatomy.

Anatomically, iatrogenic AVF after the transsylvian approach occurs at the middle cranial fossa, which usually has a venous drainage pattern involving the sphenoparietal, sphenopetrous, or sphenobasilar sinuses. Moreover, they occasionally drain directly through cortical veins or leptomeningeal veins, which results in more aggressive behavior than AVFs at other locations [7,8,23,24]. Therefore, the possibility of the AVF formation after the pterional approach should always be kept in mind and not be missed. Our case also showed middle cranial fossa AVF draining directly via SMCV, not the venous sinuses, which presented high-grade AVF leading to venous hypertension. Although it did not show intracranial hemorrhage, it was promptly treated because of its aggressiveness and patient symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

We present an extremely rare case of iatrogenic mixed pial and dural AVF that occurred after surgical clipping of a ruptured anterior choroidal artery aneurysm, which was successfully treated using an endovascular transvenous approach. AVFs acquired after the pterional approach usually occur in the middle cranial fossa and should be well recognized and promptly treated owing to their aggressiveness. Neurosurgeons should perform careful sylvian fissure dissection based on the patient-specific venous anatomy, since angioneogenesis after manipulation, retraction, and coagulation of nearby vessels may be a potential cause of iatrogenic AVF formation.

Notes

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained to publish this report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.